© Rolf Hanns

© Rolf Hanns

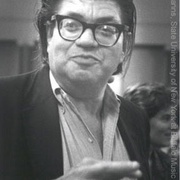

Morton Feldman

American composer born 12 January 1926 in New York City; died 3 September 1987 in Buffalo, NY.

Morton Feldman was born in Manhattan on 12 January 1926, the second son of Irving and Francis Feldman, a Jewish family that had immigrated to the United States from the Ukraine, via Warsaw. He studied piano with Vera Maurina Press, a student of Ferruccio Busoni, who had once known Alexandre Scriabine, whose influence on Feldman’s early works is clear. Press taught him “a kind of vibrant musicality, more than a musical profession.” In 1941, Feldman began studying counterpoint with Wallingford Riegger, who was a pioneer of the use of twelve-tone composing in America, although he never spoke of it in class. In 1944, Feldman began studying composition with Stefan Wolpe, who quickly arranged a meeting with Edgard Varèse, who told him, “You know, Feldman, you’ll survive. I’m not worried about you.” For many years, Feldman visited Varèse almost every week, “feeling not unlike those who make a pilgrimage to Lourdes hoping for a cure.”

In January 1950, Feldman met John Cage walking out of Carnegie Hall, where they had both gone to hear the New York Philharmonic play Anton Webern’s Symphony op. 21, conducted by Dimitri Mitropoulos. Feldman soon moved into Cage’s apartment building, Bossa’s Mansion, which was located on Grand Street, near the East River. Projection 1 (1950), for cello, was Feldman’s first venture into graphic notation. Christian Wolff, Earle Brown, and David Tudor soon formed a group around Cage and Feldman, which was perhaps somewhat hastily dubbed the “New York School” - about whom Henry Cowell wrote an article titled “Cage and His Friends” in January 1952 in The Musical Quarterly.

Feldman continued to use graphic notation in Projection 2 (1951), setting the register, dynamics, and durations while leaving the choice of pitch to the performer; later, in his Durations (1960-1961) series, he would develop what he called racecourse design, in which pitch and timbre were provided in the score, along with an overall tempo, but the musicians proceeded at their own pace, selecting durations for themselves, creating a vertical and changing sense of coordination within the piece. Not wishing his work to be taken for any kind of improvisation, he abandoned graphic notation in the period between 1953 and 1958, returned to it for some of his compositions, and then gave it up entirely, using it for the last time in 1967, with In Search of an Orchestration.

Feldman was strongly influenced by his reading of Kierkegaard the 1960s, which played a crucial role in his quest to create an art that excluded any trace of dialectic. In the 1970s, as dean of the New York Studio School (1969-1971), Feldman became interested in rugs from the Middle and Near East, which he collected, along with books and articles about them. His fascination with them was musical, and inspired what he called “crippled symmetries” or “disproportionate symmetries” which he used to “contain” his material within the metric frame of a measure.

In 1970, Feldman got to know the violist Karen Philipps, for whom he composed the series The Viola in My Life. After composing The Rothko Chapel for the non-denominational Rothko Chapel in Houston (Texas), Feldman was invited by DAAD to be an artist-in-residence in Berlin from September 1971 to October 1972, an experience he said led him to rediscover his Jewish identity. Upon his return to the United States, he was appointed the Edgard Varèse Professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo in 1973, a post he held until his death. “I’m going to have to teach them to listen.”

In 1976 Feldman returned to Berlin, where he met Samuel Beckett. Several weeks later, Beckett sent him a post card with the words to his poem neither, as a libretto for Feldman’s opéra, which premiered the following year in Rome at the Teatro dell’Opera, with staging by Michelangelo Pistoletto. Feldman dedicated two other works to Samuel Beckett in 1987 — music for a radio play titled Words and Music and For Samuel Beckett, for ensemble. As early as 1978, Feldman began writing compositions that ventured into the minutest of nuance, with no regard for convention, performability, or audience expectations; this approach reached its zenith in String Quartet (II) (1983), which lasts for nearly five hours.

Feldman continued teaching until the end of his life, notably in Germany, at the Darmstadt Summer courses (1984-1986). He died of cancer on 3 September 1987.

Feldman’s friendships with the poet Frank O’Hara, the pianist David Tudor, composers such as John Cage, Earle Brown, and Christian Wolff, and painters such as Mark Rothko, Philip Guston, Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock, Robert Rauschenberg, and Cy Twombly are reflected in the titles of many of his compositions.

© Ircam-Centre Pompidou, 2008

Morton Feldman

By Laurent Feneyrou

This text is being translated. We thank you for your patience.

« L’une de mes histoires préférées est celle d’un jeune homme qui va voir un maître Zen ; il doit rester auprès de lui sept ans, je crois. Le maître Zen lui donne un balai et, pendant sept ans, on lui dit de balayer la maison. Il balaye donc la maison ; il est là, à un endroit, et le maître est à un autre endroit avec un sabre. Le gars est là avec son balai et le maître arrive par derrière en poussant un cri perçant, en hurlant, et le jeune homme soulève son balai. Après un certain temps, le jeune homme écoute et il entend le maître se déplacer là-bas ; il se retourne alors et attend. Ou bien, il le laisse passer et se tient dans un coin ; la faculté de se mettre à l’écoute lui vient lentement. Il s’en imprègne, vous voyez. Il passe ainsi maître dans toutes les nuances de l’écoute, de la préparation et du positionnement naturel du corps, et au bout des sept années, il monte en grade. On lui reprend son balai et on lui remet un sabre1 », racontait Morton Feldman. Dans la tradition musicale européenne, ce qui est écouté est en réalité inscrit dans une structure, dans un récit ou dans un drame l’expliquant par ce qu’il n’est pas, réduisant le discours musical à une écoute de la métaphore, et entravant les possibilités mêmes de la perception. En somme, nous traduisons des faits musicaux en contenus littéraires. « Et je suis toujours d’avis que les sons sont destinés à respirer… et non pas à être mis au service d’une idée. » Feldman suggère ainsi que ce qui semble appartenir a priori au langage musical, l’écoute, est à redécouvrir.

Cette écoute, suivant l’enseignement de Varèse, dont Feldman fut comme l’élève, et dont il écrit avoir imité sinon la musique ou le style, du moins l’attitude, la « manière de vivre », est écoute du son :

a. De Charles Ives à John Cage, la tradition américaine est empirique. Le concept, la logique, les règles d’engendrement et de construction, le souci autoritaire et intimidant du faire et de la justification du geste, au détriment de l’écoute, ne suffisent pas à démontrer la validité d’une assertion musicale. Importent davantage la sensation, au pouvoir discriminant, et le souvenir, dont le propre serait la persistance. À la recherche d’une « volonté consciente de formaliser une désorientation de la mémoire », Feldman évoque les tapis turcs : si le tapis persan peut être vu à partir de chacun de ses fragments, dans le tapis turc, le dessin n’est visible que transféré dans la mémoire, excluant toute vision d’ensemble de ses tissages. Or, en musique, la forme, primitive, se basait autrefois sur une convention magnifique d’inattention, dont témoignent encore les modèles classiques : ABA, scherzo ou forme-sonate. Décrire une œuvre en réduisant ses sections à des lettres (a, b, c…), desquelles naîtrait, par leur succession, une forme, c’est manquer l’oublieuse mémoire de nos perceptions — d’où l’inadéquation d’une telle analyse à laquelle est parfois réduit l’écheveau des gestes et figures feldmaniens. Contre la religion, le caractère « thomiste » de la vérité du matériau, telle qu’elle s’exprime non chez Webern, mais chez ses continuateurs ou ses imitateurs, en tant que ce matériau y est objectal, extérieur au musicien, Varèse désigne la traversée résolue de l’expérience, brisant le diktat des structures, l’omniscience des systèmes ou des méthodes qui, avec une précision d’automate, choisissent au nom même des sons. En retour, l’esprit de la musique de Webern, dont Feldman se déclare, avec Cage, le « fils illégitime », primera sur sa dialectique sérielle : le silence ; la synthèse de l’horizontal et du vertical ; l’image en miroir, variation du rythme et de la distribution des accords dans la mesure, anticipant ainsi des symétries disproportionnées ; le motif (ou pattern) enfin, auquel Feldman reviendra tardivement.

b. « Varèse m’a donné une leçon dans la rue : ça a duré une demi-minute et ça a fait de moi un orchestrateur. Il m’a demandé : “Qu’êtes-vous en train d’écrire en ce moment, Morton ?” Je le lui racontai ; et il a dit : “Assurez-vous de bien penser au temps que cela prend, depuis la scène jusqu’ici dans le public2.” » Le son, dans l’espace, mais aussi, ce à quoi Feldman voua son enseignement : le cheminement vers la composition par le biais de la réalité acoustique, de l’instrumentation. « Connais ton instrument ! Connais-toi toi-même ! », édicte Feldman. Le son n’y met pas en valeur l’instrument et les subtilités de sa facture, lesquels, toujours disponibles, produisent ce son dans sa beauté, mais au risque de lui voler son immédiateté, de l’exagérer, de le brouiller, de le rendre à un sens, à une insistance, qui lui sont étrangers. Car il y aurait un son pur, au-delà ou en deçà de l’instrument, que la couleur, donnée a posteriori ou soulignant les articulations, transforme en un pochoir, sinon en une ressemblance fallacieuse de son.

c. Guère de protestation contre le passé, car se rebeller contre ce passé, c’est encore lui appartenir, mais une indifférence au processus historique et un intérêt pour le son en soi, car le son n’a pas d’histoire. Par l’acoustique, par la physique, Varèse, détruisant la causalité harmonique et ouvrant une autre écoute, est dans le son, comme Mondrian est dans sa toile — quoique laissent accroire ses écrits théoriques. Et l’objet sonore n’est pas dans le temps, ne disserte pas sur la nature du temps, mais existe comme temps, qu’il « projette », selon le verbe de Feldman, où résonne le dripping de Jackson Pollock, cette technique consistant à laisser s’égoutter la peinture, à l’aide de seaux percés, d’un ustensile, d’un pinceau, sur la totalité d’une toile étendue à même le sol.

d. L’insistance sur le son modifie l’appréhension de la forme : « Ses formes musicales répondent les unes aux autres, plus qu’elles entretiennent des rapports entre elles3 », écrivait Feldman de Varèse, qui serait à l’origine d’une « majesté quasi immobile », « comme un soleil qui s’immobiliserait à l’ordre d’un Josué moderne ». Selon l’essai « Symétries tronquées », il en est ainsi de l’introduction exceptionnellement longue d’*Intégrales*, créée à partir de trois notes, où Varèse utilise le schéma additif et la transformation continue des formes rythmiques et des proportions de durée. Une telle stase, conservatrice d’une tension, à l’image des toiles de Rothko, où « c’est gelé et en même temps, ça vibre », constitue l’influence majeure de la peinture sur la musique. C’est établir l’indissolubilité du son et du temps, d’où, chez Feldman, l’idée d’une œuvre comme toile temporelle. « Ce avec quoi nous tous, en tant que compositeurs, avons réellement à œuvrer, c’est le temps et le son — parfois je ne suis même pas sûr pour le son. » Moins encore le son que sa saison, ou que la durée, donc, avant l’intelligence, la rhétorique ou l’imagination, dont entend témoigner tout musicien.

L’exigence d’un retour à l’écoute nécessite comme une epoché, où l’auditeur atteint sinon l’extase, du moins le recueillement du phénomène de l’écoute sur la base de la perception du son, dans la singularité d’une notation graphique comme dans l’écriture d’usage. S’affirme la nécessité de pénétrer lentement à l’intérieur des sons, si lentement que la forme se dissipe dans la fatigue de la mémoire et se transforme en échelle, où « on laisse tout simplement courir, et puis on voit ce qui se passe ». Les mailles du temps se dénouent dans un désir d’éternité. « L’Odyssée est-elle trop longue ? », répondait Feldman à ceux qui n’y entendaient qu’ennui. L’auditeur s’imprègne de plus en plus profondément, de manière presque proustienne, de la pensée — Proust, qui d’ailleurs relierait Feldman et Samuel Beckett, l’un ayant eu connaissance de la fameuse étude de l’autre, où le temps, source de lyrisme, aboli au même titre que l’espace, donne forme à l’œuvre. Non le passé comme caillou lourd et menaçant du sentier rebattu des heures et des jours, mais la mémoire involontaire de Proust, la déflagration du souvenir nouant le présent et le passé en un commun plus essentiel que chacun des deux termes pris isolément.

Feldman remit ainsi radicalement en question le thème d’un sujet souverain qui viendrait de l’extérieur animer l’inertie des codes et des signes, et qui déposerait dans le discours la trace indélébile de sa liberté, car le créateur doit échouer pour que l’art advienne : « Vous connaissez les termites. Ces insectes qui mangent le bois. C’est très, très intéressant. Qui mâche le bois ? La termite ne peut pas le mâcher. Mais, à l’intérieur, des millions de microbes le mâchent. Il y a une analogie avec la composition : quelque chose d’autre fait le travail4. » Non plus conscience absolument libre et se posant soi-même, tel qu’il avait été défini de Descartes à Sartre, le sujet ne se constitue pas plus ici sur le fond d’une identité psychologique, mais à travers des pratiques, des écoutes et des touchers. L’œuvre de Feldman naît d’une concentration sur les résonances du piano, un piano qui l’obligeait à ralentir, et pour lequel le temps, réalité acoustique, devenait plus audible. Feldman inventa d’ailleurs une technique de jeu où le pianiste appuie silencieusement sur les touches jusqu’à un point de résistance qui libère alors un son feutré, assourdi. Toute note ainsi jouée acquiert une résonance particulièrement longue et une présence musicale qui suspendrait les exigences structurelles de la composition. En outre, la dynamique, aux confins de l’audible, élément de tension pour l’instrumentiste et pour l’auditeur, invités de la sorte à aiguiser leur attention, y contribue pleinement, soudant les timbres instrumentaux, à la lisière de l’extinction, et au risque de l’instabilité. L’écriture se concentre sur la naissance du son, en fonction de l’attaque, souvent dévoisée, sur la douceur du son et sur son mode d’extinction, même si Feldman déclarait, plus réservé : « Je ne crois même pas que ma musique soit douce… Ce qui est doux, ce sont les connexions. Ma musique est du même niveau sonore qu’un quatuor de Schubert. Si les choses semblent plus calmes, c’est parce que les liens sont plus longs. »

Loin de la variation beethovénienne, brahmsienne ou schoenbergienne, « dispositif technique merveilleux pour atteindre le maximum d’unité dans le moment », les principes de changement et de répétition, ou plutôt, de réitération aux déplacements ténus ou discrets, témoignent de la différenciation, d’une ressemblance de répétition : une surface qui sonne « comme de la répétition », à l’instar des harmonies chromatiques de trois sons ou de patterns au phrasé sans cesse modifié. Un même élément s’illumine sous un angle différent, sans que l’on sache jamais quel phénomène est l’ombre de l’autre. Dans un monde de nuances et de chromatismes gradués, où s’opère un lent dévoilement, chaque ligne énonce une même pensée, mais toujours dite autrement. L’intervalle de la variante s’apparente lointainement à celui de la traduction, que Beckett pratiqua aussi toute sa vie sur lui-même et sur d’autres. Relisons à ce titre Sébastien Chamfort, moraliste du XVIIIe siècle : « Que le cœur de l’homme est creux et plein d’ordure », et la traduction anglaise de cette épigramme, par Beckett : « How hollow heart and full of filth thou art. » Traduction et transcription musicale sont ici étroitement liées. Beckett traduit, versifie et réduit encore l’ellipse de Chamfort. Phraser, c’est être à l’écoute de ces traductions / transcriptions. Feldman le dit aussi, mais autrement : l’écriture de Beckett détermine l’infime déplacement du son. Selon le musicien, le poète écrit une phrase en français. La phrase suivante, identique, est en anglais, puis retraduite, éloignant ainsi, par une double traduction, la phrase première de la seconde : « Chaque ligne était en réalité la même pensée, dite d’une autre manière. Et pourtant la continuité donne l’impression qu’il se passe autre chose. Mais il ne se passe rien d’autre5. » La différence est si mince qu’un même motif revient, auquel il suffit désormais d’ajouter une note, un mot, ou d’en retrancher deux. Il en est de même de l’accord, mais dans un autre registre, dans une autre instrumentation, dans un autre mètre ou dans une autre nuance. « Je peux me contenter de continuellement réarranger les mêmes meubles dans la même chambre. » Seul un trait significatif subsiste, afin de rendre préhensible la filiation. La composition porte seulement sur le choix d’un motif à répéter, et pour combien de temps, ainsi que sur la nature de sa variante. Le génie du musicien, que Feldman cherchait notamment chez Beethoven, tiendra à son sens du timing, du moment exact de l’introduction d’un élément, ni avant ni après, et de sa durée, de sorte que la musique, art du temps, donne au temps son essence, en lui imprimant son tempo. Et Feldman de refuser à ses étudiants le droit d’inscrire un signe de reprise. Non, donc, la vision cauchemardesque du retour du tout, de l’identique ou du même, mais une différence, dont Feldman se fait l’exégète attentif et patient.

Comme la construction du discours ne procède ni de la variation, ni du développement, mais de cette variante, partant de l’alliance, la forme tient essentiellement du et. Une telle pensée est fondamentalement une pensée de la parataxe, le mode d’ordonnancement (taxis) selon lequel les éléments d’une phrase ne sont pas mis ensemble (sun) comme le veut la logique syntaxique, mais juxtaposés, mis à côté les uns des autres (para), en vertu d’un principe d’apposition autre que logique, et sans que le mot de liaison indique la nature du rapport entre les propositions. S’inscrivant dans une poétique du et, Feldman, qui n’eut de cesse de décliner toute tentation de causalité, au point de se définir comme un maître de l’harmonie non fonctionnelle (« master of non-functional harmony »), retrouve la construction de la phrase hébraïque procédant par courtes propositions coordonnées par la conjonction we, aux valeurs variées selon le contexte. En outre, cette construction se rattacherait à la tradition de l’exégèse juive, privilégiant l’inachevé, le partiel, l’indécis, la profusion, l’agglutinement, l’ouverture comme principe herméneutique, source de créativité permanente. D’Akiba ben Josef, maître (tanna) de l’époque de la Michnah, halakhiste qui inaugura de nouvelles méthodes d’interprétation du Livre et qui contribua ainsi à étendre sur une vaste échelle la Loi orale, de ce sage condamné à mort et exécuté à Césarée sous une horrible torture, ses chairs déchirées par les Romains à l’aide de « peignes de fer », de ce martyr qui prononça alors le dernier mot du Shema : Un (ehad), Rabbi Akiba (1963), pour soprano, flûte, cor anglais, cor, trompette, trombone, tuba, percussion et piano, ne résonne-t-il pas ? Si Hillel l’Ancien avait mis au point sept méthodes d’interprétation, rabbi Akiba, s’appuyant sur les variantes orthographiques et les particularités du Pentateuque pour en extraire des significations insoupçonnées, établit d’autres règles à partir des préfixes et des suffixes. L’œuvre de Feldman emprunte-t-elle à une telle herméneutique, visant à dévoiler le sens caché de la Bible ? N’est-ce pas aussi une manière de s’extraire du fondement moral de la variation, celui de la musique allemande du XIXe siècle, de Beethoven à Brahms, un fondement moral dont le nazisme avait ruiné les valeurs ? Avec Adorno, avec Steiner, Feldman s’interroge sur le statut de l’œuvre d’art après Auschwitz : « Je veux être le premier grand compositeur juif », disait-il.

- Morton FELDMAN, « The future of local music » (1984), dans Give My Regards to Eighth Street. Collected Writings of Morton Feldman, Cambridge, Exact Change, 2000, p. 189 ; traduction française, sous le titre « Conférence de Francfort », dans Écrits et Paroles, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1998, p. 304 (traduction légèrement modifiée).

- « The future of local music », op. cit., p. 170 ; « Conférence de Francfort », op. cit., p. 291.

- Morton FELDMAN, « Some elementary questions » (1967), dans Give My Best Regards to Eighth Street. Collected Writings of Morton Feldman, op. cit., p. 66 ; traduction française, sous le titre « Quelques questions élémentaires », dans Écrits et Paroles, op. cit., p. 178.

- Morton FELDMAN, « Darmstadt lecture » (1984), in Morton Feldman Says. Selected Interviews and Lectures 1964-1987, Londres, Hyphen Press, 2006, p. 208 ; traduction française, sous le titre « Conférence de Darmstadt », in Écrits et Paroles, op. cit., p. 335-336 (traduction légèrement modifiée).

- « Darmstadt lecture », op. cit., p. 194 ; « Conférence de Darmstadt », op. cit., p. 313.

© Ircam-Centre Pompidou, 2008

- Solo (excluding voice)

- [Composition sans titre] for piano, composed in the forties (1940), Inédit

- First Piano Sonata (in One Movement) for piano (1943), Inédit

- Andante moderato for piano (1944), Inédit

- Self-Portrait for piano (1945), Inédit

- Illusions for piano (1948), Theodore Presser

- Projection I for cello (1950), Peters

- Three Dances for piano (with drum and glass in the third movement) (1950), Inédit

- Two Intermissions for piano (1950), Peters

- Intermission III for piano (1951), Inédit

- Intersection II for piano (1951), Peters

- Nature Pieces for piano (1951), Inédit

- Variations for piano (1951), Inédit

- Extensions II for piano (1951-1952), partition retirée du catalogue

- Extensions III for piano (1952), Peters

- Intermission IV for piano (1952), Inédit

- Intermission V for piano (1952), Peters

- Piano Piece 1952 (1952), Peters

- Intermission VI for one or two pianos (1953), Peters

- Intersection + for piano (1953), Inédit

- Intersection III for piano (1953), Peters

- Intersection IV for cello (1953), Peters

- Three Pieces for Piano (1954), Peters

- Piano Piece 1955 (1955), Peters

- Piano Piece 1956 A (1956), Peters

- Piano Piece 1956 B (1956), Peters

- Last Pieces for piano (1959), Peters

- Piano Piece (to Philip Guston) (1963), Peters

- Vertical Thoughts IV for piano (1963), Peters

- Piano Piece 1964 (1964), Peters

- The King of Denmark for percussion (1964), 7 mn, Peters [program note]

- The Possibility of a New Work for Electric Guitar (1966), partition perdue

- Piano (1977), 25 mn, Universal Edition

- Principal Sound for organ (1980), 20 mn, Universal Edition [program note]

- For Aaron Copland for violin (1981), Inédit

- Triadic Memories for piano (1981), 1 h 30 mn, Universal Edition

- For Bunita Marcus for piano (1985), 1 h 15 mn, Universal Edition

- A Very Short Piece for Trumpet (1986), Universal Edition

- Palais de Mari for piano (1986), 20 mn, Universal Edition

- Chamber music

- [Composition sans titre, non datée] for horn in F, celesta and string quartet (), Inédit

- Sonata for Violin and Piano (1945), Inédit

- Sonatina for Cello and Piano (1946), Inédit

- Two Pieces for cello and piano (1948), Inédit

- Piece for Violin and Piano (1950), Peters

- [composition sans titre] for string quartet (1949-1950), Inédit

- [Composition sans titre] for two pianos and cello (1950), Inédit

- Extensions I for violin and piano (1951), Peters

- Music for the Film Jackson Pollock music for the film by Hans Namuth and Paul Falkenberg, for two cellos (1951), 7 mn, Inédit

- Projection II for five instruments (1951), Peters

- Projection III for two pianos (1951), Peters

- Projection IV for violin and piano (1951), Peters

- Structures for string quartet (1951), 6 mn, Peters

- [composition sans titre] for cello and piano (1951), Inédit

- Extensions IV for three pianos (1953), Peters

- Extensions V for two cellos (1953), partition retirée du catalogue

- Structure II for two cellos (1953), Inédit

- Two Pieces for Two Pianos (1954), 2 mn, Peters

- Three Pieces for String Quartet (1954-1956), Peters

- Two Pieces for Six Instruments (1956), Peters

- Piano (Three Hands) (1957), Peters

- Piece for Four Pianos (1957), Peters

- Two Pianos (1957), 3 mn, Peters

- Piano Four Hands (1958), Peters

- Two Instruments for horn and cello (1958), Peters

- [Composition sans titre] for two pianos (1958), Inédit

- Durations I for four instruments (1960), Peters

- Durations II for cello, piano (1960), Peters

- Durations III for tuba, violin and piano (1961), Peters [program note]

- Durations IV for vibraphone, violin and cello (1961), Peters

- Durations V for six instruments (1961), Peters

- Two Pieces for Clarinet and String Quartet (1961), Peters

- [Composition sans titre] for string quartet (1957-1962), Inédit

- De Kooning music by Willem de Kooning, film by Hans Namuth and Paul Falkenberg (1963), for five instruments (1963), 12 mn, Peters

- Vertical Thoughts 2 for violin and piano (1963), 6 mn, Peters

- Vertical Thoughts I for two pianos (1963), Peters

- [Composition sans titre] for cello (?) and piano (1964), Inédit

- Four Instruments for bells, piano, violin and cello (1965), Peters

- Two Pieces for Three Pianos (1965-1966), Peters

- False Relationships and the Extended Ending for seven instruments (1968), 16 mn, Peters

- Between Categories for eight instruments (1969), Peters

- Merce for percussion and keyboard (1963-1969), Inédit

- [Composition sans titre] for six percussions and celesta (1963-1969), Inédit

- The Viola in My Life III for viola and piano (1970), 6 mn, Universal Edition

- Three Clarinets, Cello and Piano (1971), 8 mn, Universal Edition

- Five Pianos (1972), variable, Universal Edition

- Half a Minute It's All I've Time For for four instruments (1972), Inédit

- [Composition sans titre] for three flutes (1972), Inédit

- For Frank O'Hara for six instruments (1973), 13 mn, Universal Edition

- Instruments I for five instruments (1974), 18 mn, Universal Edition

- Four Instruments for piano and string trio (1975), 6 mn, Universal Edition

- Instruments III for flute, oboe and percussion (1977), 20 mn, Universal Edition

- Spring of Chosroes for violin and piano (1977), 12 mn, Universal Edition

- Why Patterns? for flute, piano and glockenspiel (1978), 35 mn, Universal Edition

- String Quartet (1979), 1 h 40 mn, Universal Edition

- Trio for violin, cello and piano (1980), 1 h 20 mn, Universal Edition

- Bass Clarinet and Percussion (1981), 17 mn, Universal Edition

- Patterns in a Chromatic Field for cello and piano (1981), 1 h 30 mn, Universal Edition

- For John Cage for violin and piano (1982), 1 h 15 mn, Universal Edition

- Clarinet and String Quartet (1983), 45 mn, Universal Edition

- Crippled Symmetry for flute, piano and percussion (1983), 1 h 30 mn, Universal Edition

- String Quartet II (1983), between 3 h 30 mn and 5 h 30 mn, Universal Edition

- For Philip Guston for flute, piano and percussion (1984), 4 h, Universal Edition

- Piano and String Quartet (1985), 1 h 10 mn, Universal Edition

- For Christian Wolff for flute and piano (1986), 2 h, Universal Edition

- Piano, Violin, Viola, Cello (1987), 1 h 15 mn, Universal Edition

- Instrumental ensemble music

- Dirge. In Memory of Thomas Wolfe for orchestra (1943), Inédit

- Jubilee for string orchestra (1943), Inédit

- Night for string orchestra (1943), Inédit

- [composition sans titre] for string orchestra (1945), Inédit

- Episode for orchestra (1949), Inédit

- Intersection I for large orchestra (1951), Peters

- elec Marginal Intersection for orchestra (1951), Peters

- Projection V for seven instruments (1951), Peters

- Eleven Instruments for chamber ensemble (1953), Peters

- stage Ixion Summerspace, ballet for chamber ensemble or two pianos (1958), 11 mn, Peters

- Atlantis for chamber ensemble (1959), Peters

- Composition for fifteen instruments (1959), Inédit

- Instrumental Music for ensemble (1959), Inédit

- Josquin Desprez, Tu Pauperum Refugium arrangement for ensemble (1960), Inédit

- Montage 2, On the Theme of « Something Wild » with Mike Stoller, for jazz ensemble (1960), Inédit

- Montage 3, On the Theme of « Something Wild » with Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, for jazz ensemble (1960), Inédit

- Piece for Seven Instruments (1960), Inédit

- Out of « Last Pieces » for orchestra (1961), 8 mn, Peters

- The Straits of Magellan for seven instruments (1961), 5 mn, Peters

- Structures for orchestra (1960-1962), 11 mn, Peters

- Numbers for ensemble (1964), Peters

- First Principles for ensemble (1966-1967), between 12 mn and 20 mn, Peters

- In Search of an orchestration for orchestra (1967), 8 mn, Universal Edition [program note]

- [Samoa] for ensemble (1968), Inédit

- On Time and the Instrumental Factor for orchestra (1969), 8 mn, Universal Edition

- Madame Press Died Last Week at Ninety for ensemble (1970), 4 mn, Universal Edition

- I Met Heine on the Rue Furstemberg for ensemble (1971), 10 mn, Universal Edition

- Instruments II for ensemble (1975), 18 mn, Universal Edition

- Music for a Film on Seymour Lipton (1975), Inédit

- Orchestra for orchestra (1976), 18 mn, Universal Edition

- Routine Investigations for six instruments (1976), 16 mn, Universal Edition

- The Turfan Fragments for orchestra (1980), 17 mn, Universal Edition

- Coptic Light for orchestra (1985), 30 mn, Universal Edition

- For Samuel Beckett for ensemble (1987), 55 mn, Universal Edition

- Samuel Beckett, Words and Music music for the radio piece, for seven instruments (1987), 40 mn, Universal Edition

- Concertant music

- [composition sans titre] for solo cello, woodwinds written in groups, violin, viola (1952), Inédit

- The Viola in My Life I for viola and five instruments (1970), 10 mn, Universal Edition

- The Viola in My Life II for viola and six instruments (1970), 12 mn, Universal Edition

- The Viola in My Life IV for viola and orchestra (1971), 20 mn, Universal Edition

- Cello and Orchestra (1972), 19 mn, Universal Edition

- String Quartet and Orchestra (1973), 22 mn, Universal Edition

- Piano and Orchestra (1975), 21 mn, Universal Edition

- Oboe and Orchestra (1976), 18 mn, Universal Edition

- Flute and Orchestra (1978), 35 mn, Universal Edition

- Violin and Orchestra (1979), 1 h 5 mn, Universal Edition

- Violin and String Quartet (1985), 1 h 30 mn, Universal Edition

- Vocal music and instrument(s)

- Kurt Weill, Alabama Song arrangement for ensemble and voices ad libitum (), Inédit

- I loved you once for voice and string quartet (1940), Inédit

- Journey to the End of the Night for soprano and four instruments (1947), Peters

- Lost Love for voice and piano (1949), Inédit

- Four Songs to e. e. cummings for soprano, piano and cello (1951), Peters

- Three Ghost-Like Songs and Interlude for voice, trombone, piano, viola (1951), Inédit

- The Swallows of Salangan for choir and ensemble (1960), 15 mn, Peters

- Wind for singing voice and piano (1960), Inédit

- Intervals for bass-baritone and ensemble (1961), Peters

- Followe The Faire Sunne for voice and tubular bells (1962), Inédit

- For Franz Kline for soprano and five instruments (1962), Peters

- The O'Hara Songs for bass-baritone and five instruments (1962), Peters

- Chorus and Instruments for mixed choir and ensemble (1963), Peters

- Rabbi Akiba for soprano and ensemble (1963), Peters

- Vertical Thoughts III for soprano and ensemble (1963), Peters

- Vertical Thoughts V for soprano, and four instruments (1963), Peters

- Chorus and Instruments 2 for mixed choir, tuba and bells (1967), Peters

- Chorus and Orchestra 1 for soprano, mixed double choir and orchestra (1971), 15 mn, Universal Edition

- The Rothko Chapel for soprano, contralto, double choir and three instruments (1971), 30 mn, Universal Edition [program note]

- Chorus and Orchestra II for soprano, mixed double choir and orchestra (1972), 22 mn, Universal Edition

- Pianos and Voices for five sopranos and five pianos (1972), Universal Edition

- Voice and Instruments for soprano and chamber orchestra (1972), 15 mn, Universal Edition

- Voices and Instruments for mixed choir and ensemble (1972), 11 mn, Universal Edition

- Voices and Instruments II for three high-pitched voices and four instruments (1972), 12 mn, Universal Edition

- Voices and Cello for two high-picthed voices and cello (1973), 7 mn, Universal Edition [program note]

- Voice and Instruments II for voice and three instruments (1974), 9 mn, Universal Edition

- Elemental Procedures for soprano, choir and orchestra (1976), 20 mn, Universal Edition

- Voice, Violin and Piano (1976), 5 mn, Universal Edition

- stage Neither one-act opera, for soprano and orchestra (1976-1977), 1 h 10 mn, Universal Edition

- [Composition sans titre] for voice, clarinet, cello and double bass (1970-1977), Inédit

- For Stefan Wolpe for mixed choir and two vibraphones (1986), 38 mn, Universal Edition

- A cappella vocal music

- Only for female voice (1946), 60 s, Universal Edition

- Christian Wolff in Cambridge for mixed choir a cappella (1963), Peters

- elec Three Voices for soprano and tape (or three sopranos) (1982), 1 h 30 mn, Universal Edition [program note]

- Electronic music / fixed media / mechanical musical instruments

- [Sweeney Agonistes] for amplified clock ticking, on Sweeney Agonistes by T.S. Eliot (1952), Inédit

- Intersection for Magnetic Tape for eight-track magnetic tape (1953), Peters

- Unspecified instrumentation

- [Musique de film sans titre, non datée] (), Inédit

- Score for Untitled Film (1960), Inédit

- [Mélodie sans titre pour Merce Cunningham] (1968), Inédit

- 1987

- For Samuel Beckett for ensemble, 55 mn, Universal Edition

- Piano, Violin, Viola, Cello, 1 h 15 mn, Universal Edition

- Samuel Beckett, Words and Music music for the radio piece, for seven instruments, 40 mn, Universal Edition

- 1986

- A Very Short Piece for Trumpet, Universal Edition

- For Christian Wolff for flute and piano, 2 h, Universal Edition

- For Stefan Wolpe for mixed choir and two vibraphones, 38 mn, Universal Edition

- Palais de Mari for piano, 20 mn, Universal Edition

- 1985

- Coptic Light for orchestra, 30 mn, Universal Edition

- For Bunita Marcus for piano, 1 h 15 mn, Universal Edition

- Piano and String Quartet, 1 h 10 mn, Universal Edition

- Violin and String Quartet, 1 h 30 mn, Universal Edition

- 1984

- For Philip Guston for flute, piano and percussion, 4 h, Universal Edition

- 1983

- Clarinet and String Quartet, 45 mn, Universal Edition

- Crippled Symmetry for flute, piano and percussion, 1 h 30 mn, Universal Edition

- String Quartet II, between 3 h 30 mn and 5 h 30 mn, Universal Edition

- 1982

- For John Cage for violin and piano, 1 h 15 mn, Universal Edition

- elec Three Voices for soprano and tape (or three sopranos), 1 h 30 mn, Universal Edition [program note]

- 1981

- Bass Clarinet and Percussion, 17 mn, Universal Edition

- For Aaron Copland for violin, Inédit

- Patterns in a Chromatic Field for cello and piano, 1 h 30 mn, Universal Edition

- Triadic Memories for piano, 1 h 30 mn, Universal Edition

- 1980

- Principal Sound for organ, 20 mn, Universal Edition [program note]

- The Turfan Fragments for orchestra, 17 mn, Universal Edition

- Trio for violin, cello and piano, 1 h 20 mn, Universal Edition

- 1979

- String Quartet, 1 h 40 mn, Universal Edition

- Violin and Orchestra, 1 h 5 mn, Universal Edition

- 1978

- Flute and Orchestra, 35 mn, Universal Edition

- Why Patterns? for flute, piano and glockenspiel, 35 mn, Universal Edition

- 1977

- Instruments III for flute, oboe and percussion, 20 mn, Universal Edition

- stage Neither one-act opera, for soprano and orchestra, 1 h 10 mn, Universal Edition

- Piano, 25 mn, Universal Edition

- Spring of Chosroes for violin and piano, 12 mn, Universal Edition

- [Composition sans titre] for voice, clarinet, cello and double bass, Inédit

- 1976

- Elemental Procedures for soprano, choir and orchestra, 20 mn, Universal Edition

- Oboe and Orchestra, 18 mn, Universal Edition

- Orchestra for orchestra, 18 mn, Universal Edition

- Routine Investigations for six instruments, 16 mn, Universal Edition

- Voice, Violin and Piano, 5 mn, Universal Edition

- 1975

- Four Instruments for piano and string trio, 6 mn, Universal Edition

- Instruments II for ensemble, 18 mn, Universal Edition

- Music for a Film on Seymour Lipton, Inédit

- Piano and Orchestra, 21 mn, Universal Edition

- 1974

- Instruments I for five instruments, 18 mn, Universal Edition

- Voice and Instruments II for voice and three instruments, 9 mn, Universal Edition

- 1973

- For Frank O'Hara for six instruments, 13 mn, Universal Edition

- String Quartet and Orchestra, 22 mn, Universal Edition

- Voices and Cello for two high-picthed voices and cello, 7 mn, Universal Edition [program note]

- 1972

- Cello and Orchestra, 19 mn, Universal Edition

- Chorus and Orchestra II for soprano, mixed double choir and orchestra, 22 mn, Universal Edition

- Five Pianos, variable, Universal Edition

- Half a Minute It's All I've Time For for four instruments, Inédit

- Pianos and Voices for five sopranos and five pianos, Universal Edition

- Voice and Instruments for soprano and chamber orchestra, 15 mn, Universal Edition

- Voices and Instruments for mixed choir and ensemble, 11 mn, Universal Edition

- Voices and Instruments II for three high-pitched voices and four instruments, 12 mn, Universal Edition

- [Composition sans titre] for three flutes, Inédit

- 1971

- Chorus and Orchestra 1 for soprano, mixed double choir and orchestra, 15 mn, Universal Edition

- I Met Heine on the Rue Furstemberg for ensemble, 10 mn, Universal Edition

- The Rothko Chapel for soprano, contralto, double choir and three instruments, 30 mn, Universal Edition [program note]

- The Viola in My Life IV for viola and orchestra, 20 mn, Universal Edition

- Three Clarinets, Cello and Piano, 8 mn, Universal Edition

- 1970

- Madame Press Died Last Week at Ninety for ensemble, 4 mn, Universal Edition

- The Viola in My Life I for viola and five instruments, 10 mn, Universal Edition

- The Viola in My Life II for viola and six instruments, 12 mn, Universal Edition

- The Viola in My Life III for viola and piano, 6 mn, Universal Edition

- 1969

- Between Categories for eight instruments, Peters

- Merce for percussion and keyboard, Inédit

- On Time and the Instrumental Factor for orchestra, 8 mn, Universal Edition

- [Composition sans titre] for six percussions and celesta, Inédit

- 1968

- False Relationships and the Extended Ending for seven instruments, 16 mn, Peters

- [Mélodie sans titre pour Merce Cunningham], Inédit

- [Samoa] for ensemble, Inédit

- 1967

- Chorus and Instruments 2 for mixed choir, tuba and bells, Peters

- First Principles for ensemble, between 12 mn and 20 mn, Peters

- In Search of an orchestration for orchestra, 8 mn, Universal Edition [program note]

- 1966

- The Possibility of a New Work for Electric Guitar, partition perdue

- Two Pieces for Three Pianos, Peters

- 1965

- Four Instruments for bells, piano, violin and cello, Peters

- 1964

- Numbers for ensemble, Peters

- Piano Piece 1964, Peters

- The King of Denmark for percussion, 7 mn, Peters [program note]

- [Composition sans titre] for cello (?) and piano, Inédit

- 1963

- Chorus and Instruments for mixed choir and ensemble, Peters

- Christian Wolff in Cambridge for mixed choir a cappella, Peters

- De Kooning music by Willem de Kooning, film by Hans Namuth and Paul Falkenberg (1963), for five instruments, 12 mn, Peters

- Piano Piece (to Philip Guston), Peters

- Rabbi Akiba for soprano and ensemble, Peters

- Vertical Thoughts 2 for violin and piano, 6 mn, Peters

- Vertical Thoughts I for two pianos, Peters

- Vertical Thoughts III for soprano and ensemble, Peters

- Vertical Thoughts IV for piano, Peters

- Vertical Thoughts V for soprano, and four instruments, Peters

- 1962

- Followe The Faire Sunne for voice and tubular bells, Inédit

- For Franz Kline for soprano and five instruments, Peters

- Structures for orchestra, 11 mn, Peters

- The O'Hara Songs for bass-baritone and five instruments, Peters

- [Composition sans titre] for string quartet, Inédit

- 1961

- Durations III for tuba, violin and piano, Peters [program note]

- Durations IV for vibraphone, violin and cello, Peters

- Durations V for six instruments, Peters

- Intervals for bass-baritone and ensemble, Peters

- Out of « Last Pieces » for orchestra, 8 mn, Peters

- The Straits of Magellan for seven instruments, 5 mn, Peters

- Two Pieces for Clarinet and String Quartet, Peters

- 1960

- Durations I for four instruments, Peters

- Durations II for cello, piano, Peters

- Josquin Desprez, Tu Pauperum Refugium arrangement for ensemble, Inédit

- Montage 2, On the Theme of « Something Wild » with Mike Stoller, for jazz ensemble, Inédit

- Montage 3, On the Theme of « Something Wild » with Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, for jazz ensemble, Inédit

- Piece for Seven Instruments, Inédit

- Score for Untitled Film, Inédit

- The Swallows of Salangan for choir and ensemble, 15 mn, Peters

- Wind for singing voice and piano, Inédit

- 1959

- Atlantis for chamber ensemble, Peters

- Composition for fifteen instruments, Inédit

- Instrumental Music for ensemble, Inédit

- Last Pieces for piano, Peters

- 1958

- stage Ixion Summerspace, ballet for chamber ensemble or two pianos, 11 mn, Peters

- Piano Four Hands, Peters

- Two Instruments for horn and cello, Peters

- [Composition sans titre] for two pianos, Inédit

- 1957

- Piano (Three Hands), Peters

- Piece for Four Pianos, Peters

- Two Pianos, 3 mn, Peters

- 1956

- Piano Piece 1956 A, Peters

- Piano Piece 1956 B, Peters

- Three Pieces for String Quartet, Peters

- Two Pieces for Six Instruments, Peters

- 1955

- Piano Piece 1955, Peters

- 1954

- Three Pieces for Piano, Peters

- Two Pieces for Two Pianos, 2 mn, Peters

- 1953

- Eleven Instruments for chamber ensemble, Peters

- Extensions IV for three pianos, Peters

- Extensions V for two cellos, partition retirée du catalogue

- Intermission VI for one or two pianos, Peters

- Intersection + for piano, Inédit

- Intersection III for piano, Peters

- Intersection IV for cello, Peters

- Intersection for Magnetic Tape for eight-track magnetic tape, Peters

- Structure II for two cellos, Inédit

- 1952

- Extensions II for piano, partition retirée du catalogue

- Extensions III for piano, Peters

- Intermission IV for piano, Inédit

- Intermission V for piano, Peters

- Piano Piece 1952, Peters

- [Sweeney Agonistes] for amplified clock ticking, on Sweeney Agonistes by T.S. Eliot, Inédit

- [composition sans titre] for solo cello, woodwinds written in groups, violin, viola, Inédit

- 1951

- Extensions I for violin and piano, Peters

- Four Songs to e. e. cummings for soprano, piano and cello, Peters

- Intermission III for piano, Inédit

- Intersection I for large orchestra, Peters

- Intersection II for piano, Peters

- elec Marginal Intersection for orchestra, Peters

- Music for the Film Jackson Pollock music for the film by Hans Namuth and Paul Falkenberg, for two cellos, 7 mn, Inédit

- Nature Pieces for piano, Inédit

- Projection II for five instruments, Peters

- Projection III for two pianos, Peters

- Projection IV for violin and piano, Peters

- Projection V for seven instruments, Peters

- Structures for string quartet, 6 mn, Peters

- Three Ghost-Like Songs and Interlude for voice, trombone, piano, viola, Inédit

- Variations for piano, Inédit

- [composition sans titre] for cello and piano, Inédit

- 1950

- Piece for Violin and Piano, Peters

- Projection I for cello, Peters

- Three Dances for piano (with drum and glass in the third movement), Inédit

- Two Intermissions for piano, Peters

- [Composition sans titre] for two pianos and cello, Inédit

- [composition sans titre] for string quartet, Inédit

- 1949

- 1948

- Illusions for piano, Theodore Presser

- Two Pieces for cello and piano, Inédit

- 1947

- Journey to the End of the Night for soprano and four instruments, Peters

- 1946

- Only for female voice, 60 s, Universal Edition

- Sonatina for Cello and Piano, Inédit

- 1945

- Self-Portrait for piano, Inédit

- Sonata for Violin and Piano, Inédit

- [composition sans titre] for string orchestra, Inédit

- 1944

- Andante moderato for piano, Inédit

- 1943

- Dirge. In Memory of Thomas Wolfe for orchestra, Inédit

- First Piano Sonata (in One Movement) for piano, Inédit

- Jubilee for string orchestra, Inédit

- Night for string orchestra, Inédit

- 1940

- I loved you once for voice and string quartet, Inédit

- [Composition sans titre] for piano, composed in the forties, Inédit

- Date de composition inconnue

- Kurt Weill, Alabama Song arrangement for ensemble and voices ad libitum, Inédit

- [Composition sans titre, non datée] for horn in F, celesta and string quartet, Inédit

- [Musique de film sans titre, non datée], Inédit

Bibliographie

- Musik-Konzepte, mai 1986, n° 48-49 (sous la direction de Heinz-Klaus Metzger et Rainer Riehn).

- MusikTexte, décembre 1987, n° 22, et janvier 1994, n° 52.

- Sebastian CLAREN, Neither. Die Musik Morton Feldmans, Hofheim, Wolke Verlag, 2000.

- John CAGE, Silence. Conférences et écrits (1961), Genève, Héros-Limite, 2003.

- John CAGE et Morton FELDMAN, Radio Happening (1966-1967), Cologne, MusikTexte, 1993.

- The Music of Morton Feldman (sous la direction de Thomas DeLio), New York, Excelsior Publishing Company, 1996.

- Morton FELDMAN, Essays (sous la direction de Walter Zimmermann), Kerpen, Beginner Press, 1985.

- Morton FELDMAN, Écrits et Paroles (sous la direction de Jean-Yves Bosseur), Paris, L’Harmattan, 1998.

- Morton FELDMAN, Give my Best Regards to Eighth Street. Collected Writings of Morton Feldman (sous la direction de B.H. Friedman), Cambridge, Exact Change, 2000.

- Morton Feldman Says, Selected Interviews and Lectures 1964-1987 (sous la direction de Chris Villars), Londres, Hyphen Press, 2006.

- Philip GAREAU, La Musique de Morton Feldman ou le temps en liberté, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2006.

- Suzanne JOSEK, The New York School : Earle Brown, John Cage, Morton Feldman, Christian Wolff, Sarrebruck, Pfau, 1998.

- Marion SAXER, Between Categories : Studien zum Komponieren Morton Feldmans von 1951 bis 1977, Sarrebruck, Pfau, 1998.

Discographie

- Morton FELDMAN, Three Voices, Joan La Barbara : soprano, 1 cd New Albion Records, 1989, NA018.

- Morton FELDMAN, Triadic Memories ; Piano ; Two Pianos ; Piano Four Hands ; Piano (Three Hands), Roger Woodward : piano, 2 cds Etcetera, 1991, KTC 2015.

- Morton FELDMAN, Why Patterns ? ; Crippled Symmetry, Eberhard Blum : flûte, Nils Vigeland : piano et célesta, Jan Williams : percussion, 2 cds Hat Hut, 1991, Hat ART 2-60801-2.

- Morton FELDMAN, For Christian Wolff, Eberhard Blum : flûte, Nils Vigeland : piano et célesta, 3 cds Hat Hut, 1992, Hat ART 3-61201-3.

- Morton FELDMAN, For Philip Guston, Eberhard Blum : flûte, Nils Vigeland : piano et célesta, Jan Williams : percussion, 4 cds Hat Hut, 1992, Hat ART 4-61041-4.

- Morton FELDMAN, Routine Investigations ; The Viola in My Life 1 ; The Viola in My Life 2 ; For Frank O’Hara ; I Met Heine on the Rue Fürstenberg, Ensemble Recherche, 1 cd Auvidis-Montaigne, 1994, MO782018.

- Morton FELDMAN, For Bunita Marcus, Markus Hinterhäuser : piano, 1 cd Col legno, 1995, WWE31886.

- Morton FELDMAN, Words and Music, Omar Ebrahim et Stephen Lind : voix, Ensemble Recherche, 1 cd Auvidis-Montaigne, 1996, MO782084.

- Morton FELDMAN, Neither, Sarah Leonard : soprano, Radio-Sinfonie-Orchester Frankfurt, direction : Zoltán Peskó, 1 cd Hat Hut, 1997, Hat[now]ART 102.

- Morton FELDMAN, Flute and Orchestra ; Cello and Orchestra ; Oboe and Orchestra ; Piano and Orchestra, Roswitha Staege : flûte (I), Siegfried Palm : violoncelle (II), Armin Aussem : hautbois (III), Roger Woodward : piano (IV), Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Saarbrücken, direction : Hans Zender, 2 cds cpo, 1997, 999 483-2.

- Morton FELDMAN, For Samuel Beckett, Klangforum Wien, direction : Sylvain Cambreling, 1 cd Kairos, 1999, 0012012KAI.

- Morton FELDMAN, String Quartet (II), Ives Ensemble, 4 cds Hat Hut, 2001, Hat[now]ART 4-144.

- Morton FELDMAN, The Rothko Chapel ; For Stephan Wolpe ; Christian Wolff in Cambridge, SWR Vokalenensemble Stuttgart, direction : Rupert Huber, 1 cd Hänssler, 2002, 93.023.

- Morton FELDMAN, Violin and Orchestra ; Coptic Light, Isabelle Faust : violon (I), Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, direction : Peter Rundel, 1 cd Col legno, 2004, WWE 20089.

- Morton FELDMAN, Only ; Projection 1 ; Projection 2 ; Projection 3 ; Projection 4 ; Projection 5 ; Intersection 2 ; Intersection 3 ; Intersection 4 ; Piece for Four Pianos ; Two Pianos ; Piano Four Hands, Piano Piece 1964 ; Durations 1 ; Durations 2 ; Durations 3 ; Durations 4 ; Durations 5 ; Vertical Thoughts 1 ; Vertical Thoughts 2 ; Vertical Thoughts 3 ; Vertical Thoughts 4 ; Vertical Thoughts 5 ; Voice and Instruments II ; Instruments I ; Voice ; Violon and Piano ; Instruments III ; Bass Clarinet and Percussion, The Barton Workshop, 3 cds Etcetera, 1997, KTC 3003.

Site Internet

- Morton Feldman Page, http://www.cnvill.net/mfhome.htm, vérifié en septembre 2013.